Plant in box containers

Very severe cargo damage, right up to total loss, is inevitable here:

|

On a ship, heel angles of 30° are not unusual during rolling. These heeling angles are also commensurate with the lateral acceleration forces of 0.5 g in road and rail transport.

|

|

Although attempts have been made to restrain the cargo at floor level using squared lumber, no thought was given to the fact that the cargo is at risk of tipping over and toppling out of these restraints during transit under the above-mentioned conditions.

|

Provided that machines or plant parts that are unpackaged or are wrapped only in a sealed package for corrosion protection are attached to a base or frame of sufficient loading capacity, securing of such cargoes is relatively simple and cost-effective.

|

The shipping packages are introduced into the container and any gaps are filled with wedges (1) or fixed in the base area with squared lumber. Securing against tipping and also against shifting in all directions can be achieved by shoring.

|

When producing the package bases, care must be taken to ensure that the bottom joists run lengthwise, so that the cargo weight can be transmitted uniformly to the container bottom cross members. Appropriately cut squared lumber is laid across the package bases or frames at several points (2). "Shoring" (3) is fitted between this lumber and the container's top side rails and knocked outwards slightly in the bottom area in order to exert sufficient pressure on the "wooden pressure members" (2). Finally, "wooden securing members" (4) are nailed on, with the purpose of holding the shoring in place throughout the journey.

If there is concern that shoring may shift in the longitudinal direction, it may be stopped from doing this by nailing wooden bars on to it. Better results can be achieved with wood connectors. However, using wood connectors is more expensive with regard to nailing, since thought has also to be given to removal of the cargo from the container - detaching wood connectors is more difficult than detaching boards.

|

|

|

|

| Securing with board ends | Securing with flat wood connectors | Securing with angular wood connectors |

The risk of damage to the cargo and the costs are reduced if wood connectors are screwed on by machine, so avoiding powerful hammer blows to detach the nailed-down lumber.

In the case of containers with corrugated walls, slippage of the shoring in the upper area may be ruled out by arranging it in the corrugations. The same applies to the wooden pressure members, which may also fit into the corrugations. In the case of smooth or inadequately profiled container walls, however, the lumber must be made more secure by "X-bracing".

|

|

| 2 = wooden pressure members, 3 = shoring, 5 = X-bracing boards, 6 = wooden bracing |

Plant parts and accessories in a container

The entire container is lined with a film, to protect the contents from moisture and thus from corrosion. The film shown cannot achieve this.

|

|

| Container packed with plant parts |

The film has been damaged by introduction of the cargo, through being walked over by the loading personnel and by nailing of the joists and securing lumber to the container floor and it therefore no longer functions as a barrier. Even if the barrier were still intact, the lumber introduced in large quantities is such a source of moisture that the water vapor released by it could only be absorbed if enormous quantities of desiccants were introduced.

Only if kiln dry lumber is used and it can be guaranteed that the barrier remains undamaged can reliable corrosion protection be achieved in this manner.

The following details relate only to mechanical cargo securing, irrespective of the efficacy of any attempts to achieve corrosion protection.

Lining of the container with film makes all the lashing points inaccessible. The remaining cargo securing options are therefore primarily only compact loading and gap filling. As a secondary option, lashings can be attached to the fixed lumber or wooden frames.

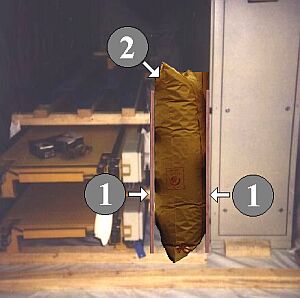

The switch cabinet is not yet secured. The gap can be filled with cargo, braced or closed up with airbags.

|

|

| Gap closed with airbag |

To prevent harmful deformation of the sheet metal switch cabinet body and the other items of cargo and to protect the airbag from damage, two plywood boards or the like (1) are positioned to the left and right in the gap. The airbag (2) is positioned in between them and inflated.

A wooden frame was prepared for securing lubricant barrels.

|

|

| Wooden frame for lubricant barrels |

|

|

| Securing cargo to wooden frames |

The lubricant barrels were positioned on the base frame (a) introduced into the container and fixed in the base frame by planks nailed crosswise in front of them. A further frame (b) was positioned on the barrels, over which straps (c) were tightened to secure the barrels vertically and against tipping. The plant parts (d) were also fixed in a wooden frame with straps (e) and the same was done for part (f). In principle, such securing is possible if the frames themselves cannot be levered out by the lashings or tip over together with their attachments. It is therefore essential to secure the frames against upward movement. Since container roofs have only a low loading capacity, shoring against the top side rails is again an option. Without these additional measures, the cargo will be damaged.