|

|

| View of a container terminal - Bremerhaven in this case |

The definition stated in the CTU packing guidelines for handling reads:

-

Handling includes the operation of loading or unloading/discharging of a ship, railway wagon [rail car], vehicle or other means of transport (CTUs).

-

Ship means a seagoing or non-seagoing watercraft, including those used on inland waters.

- stresses which act on an empty or packed cargo transport unit due to the use of suitable equipment when handling the whole CTU and those

- stresses which arise during packing and unpacking of the containers by manual methods and/or by using mechanical aids and equipment.

|

Handling a container with a reachstacker and top spreader |

| Transferring barrels into a container with a forklift truck and barrel lifter |  |

The CTU packing guidelines define a forklift truck as follows:

-

Forklift truck means a truck equipped with devices such as arms, forks, clamps, hooks, etc. to handle any kind of cargo, including cargo that is unitized, overpacked or packed in CTUs.

- avoidable stresses and

- unavoidable stresses

|

|

| Avoidable cargo handling stresses during unpacking of a container |

Packing and unpacking containers or other cargo transport units involves procedures which are no different from those previously used in conventional loading - the same risks are encountered and must be taken into account. Purely manual handling of packages generally entails exposure to more impact and dropping than in the case of mechanized handling using tried and tested industrial aids. Properly packaged and palletized goods are at little risk when forklift trucks and similar ground conveyors are used. The risk is distinctly greater for incorrectly packaged and palletized goods. However, if personnel are untrained, the risks associated with the use of mechanical aids are particularly high.

|

Avoidable handling stress during container handling with a forklift truck |

In this case, the attempt had been made to use a forklift truck to position a flatrack. In attempting to get the tines of a forklift truck under the flatrack and shift it, the fork slipped off, bending the side rail and puncturing the flatrack.

|

|

|

| Avoidable handling stresses | ||

If containers are handled with the equipment specially developed for this purpose, the impact stresses to which the various cargo transport units are exposed are comparatively uniform, irrespective of whether they are being transferred between road or rail vehicles or watercraft.

The CTU packing guidelines also provide some indications about cargo handling:

-

1.8 Container movements by terminal tractors may be subject to differing forces as terminal trailers are not equipped with suspension. Additionally, ramps can be very steep, causing badly stowed cargo inside CTUs to be thrown forward or backward.

|

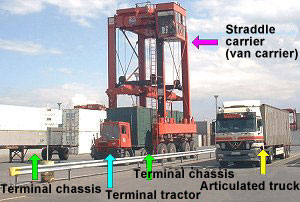

Cargo handling activities at a seaport terminal |

Terminal tractors (Tugmaster units) and terminal chassis are normally only used for moving containers on the flat. Various methods are used in terminals for this purpose. With regard to ramps, the guidelines relate to ro/ro tractors in conjunction with roll trailers. Both types of tractor require a hydraulically liftable fifth wheel coupling to allow access to the ramps. The normal chassis or semitrailers pulled by the tractors have suspension.

The stated effects on badly packed cargo have already been mentioned several times.

|

|

|

| Ship/shore transfer with container gantry cranes and fully automatic spreaders |

||

|

|

|

| Intermodal cargo transfer with grapplers on a reachstacker and a gantry crane |

||

The CTU packing guidelines also provide some information about the use of lifting gear and ground conveyors:

-

1.9 Considerable forces may also be exerted on CTUs and their cargoes during terminal transfer. Especially in seaports, containers are transferred by shore-side gantry cranes that lift and lower containers, applying considerable acceleration forces and creating pressure on the packages in containers. Lift trucks and straddle carriers may take containers, lift them, tip them and move them across the terrain of the terminal.

|

Deformed container floor due to the interplay of acceleration and incorrect packing methods |

Even when equipment is expertly operated, stresses of approx. 1 g must generally be anticipated during cargo handling. Skilled operation assumes that the goods are lifted up and set down gently. Jerky lifting and setting down may generate very much higher g values.

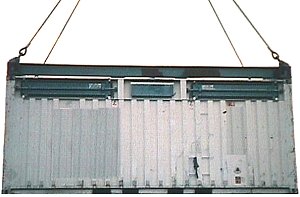

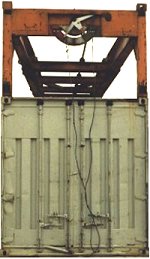

Normal setting down impacts cannot always be avoided and additional crush pressures must thus always be expected. This applies both to setting down the receptacle and to setting down the spreader on the containers. If spreaders without flippers are used carelessly (the flippers center the spreader on the container), damage to container roofs must be expected. There is still a risk of damage even when manual spreaders or "overheight frames" are used.

|

Handling with manual spreader |

|

|

|

| Right and left: Overheight frame with manual locking (in this case only set down on the container) |

||

Especially in the case of onward carriage in countries with poor infrastructure, higher levels of stress must be anticipated during handling and unloading operations. So that no damage is caused during unpacking of the cargo transport units, packing must always be designed in such a way that the containers can be stripped as simply as possible.

|

|

| Handling with on-shore container gantry cranes |

It is also to be expected that containers will not always be handled as properly as they are here, but that during onward carriage they may possibly be unloaded under the most basic conditions from an old ship in the roads. "Bumping" against obstructions is not at all unusual under such circumstances. Packing and securing should be designed to withstand such occurrences.

|

Individual containers on an old design general cargo ship - in the roads |

Handling stresses during packing and unpacking of containers are generally the result of carelessness. It is not unusual for:

- personnel to walk on cargo which cannot withstand such loads;

- packages to be dropped during manual working;

- poorly packed pallets to come apart during forklift truck operations and for individual packages to fall out;

- packages to be punctured with the forks;

- packages to be crushed or squashed with the forklift truck;

- damage to be caused by the use of tools and cargo securing materials etc.

|

|

|

| The carton has already been crushed to 2/3 of its original dimensions. |

||

Another case of human failure due to inadequate skills and insufficient supervision.

|

Stowing symbol: Do not walk here! |

The cargo could be marked with a stowing symbol like this.