Introductory remarks

This section is intended to provide the interested layperson with some basic information about how to stow and secure containers on board ocean-going vessels, so as to give him/her a better idea of the problems involved and possibly of how to select the appropriate carrier. Those actually involved with securing containers on board ships should refer to other specialist literature.

General on-board stowage

On most ships which are specially designed for container traffic, the containers are carried lengthwise:

|

Containers stowed lengthwise fore and aft stowage on board a ship |

This stowage method is sensible with regard to the interplay of stresses in rough seas and the loading capacity of containers. Stresses in rough seas are greater athwartships than fore and aft and the loading capacity of container side walls is designed to be higher than that of the end walls.

However, on many ships the containers are stowed in athwartships bays or are transported athwartships for other reasons. This must be taken into consideration when packing containers and securing cargo.

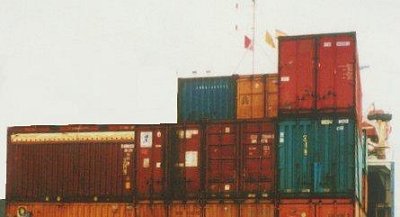

|

|

| Containers stowed athwartships (athwartships stowage) on board a ship |

This stowage method is not sensible with regard to the stresses in rough seas and the loading capacity of containers. Stresses in rough seas are greater athwartships than fore and aft but the loading capacity of container end walls is lower than that of the side walls.

|

|

| Containers stowed both ways on board ship |

Even unusual stowage methods like this, where some of the containers are stowed athwartships and others fore and aft, are used, but they require greater effort during packing and securing operations.

The above two pictures show how important it is to find out about the various carriers and their way of transporting containers, either in order to rule out certain modes of transport or to be able to match cargo securing to mode of transport. If the method of transporting a container is not known, then packing and securing have to be geared to the greater stresses.

General securing information

When securing containers on board, the stresses resulting from the ship's movements and wind pressure must be taken into account. Forces resulting from breaking-wave impact can only be taken into account to a certain degree. All the containers on board must be secured against slippage and toppling, with care being taken to ensure that the load-carrying parts of the containers are not loaded beyond admissible levels.

Except in the case of individually carried containers, securing is effected by stacking the containers in vertical guide rails or by stowing them in stacks or blocks, the containers being connected together and fixed to parts of the vessel.

Securing in vessel holds by cell guides alone

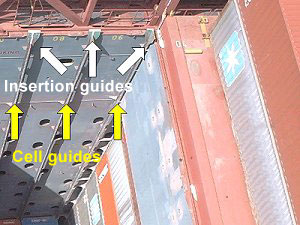

|

Cell guides in an all-container ship |

Virtually all all-container ships are provided with cell guides with vertical guide rails as securing means for hold cargoes. The greatest stress the containers are exposed to stems from stack pressure. Since the containers are not connected together vertically, lateral stress is transmitted by each individual container to the cell guides When positioned in such cell guides, individual containers are not usually able to shift. If the corner posts of one of the containers at the bottom of a stack collapse under excessive pressure, containers stowed above it generally suffer only slight damage. The risk of damage to containers in adjacent stacks is kept within tight limits.

| Guide rails of two adjacent slots |  |

The containers are guided by these rails of the cell guides during loading and unloading. The photo shows clearly that the upper ends of the guide rails each take the form of insertion guides.

Securing in vessel holds by cell guides and pins

Feeder ships, multipurpose freighters and container ships in certain regions have to be particularly flexibly equipped, in order to be able to carry containers of different dimensions. To this end, convertible stowage frames have been developed, in which 20', 24½', 30', 40', 45', 48' and 49' containers may be stowed securely without appreciable delay.

Most of these frames are produced as panels which are brought into the required positions by cranes. At the bottom they mainly have fixed cones, which engage in pockets welded into the tank top area. At the sides, the frames are secured by pins, which engage in bushes which are let into the wing bulkheads. Such frames are often man-accessible, so that the containers can be locked in place by means of pins.

If it is necessary to be able to carry containers 2,500 mm wide, the frames are arranged on the basis of this dimension. To secure standard containers of normal width, closure rails are then fitted on both sides of the guide rails by means of screw connections. If necessary, these adapters may be removed.

Removable container guides have also been developed and constructed for multipurpose freighters, reefer vessels and the like. Such guides allow containers to be carried in regular or insulated holds without any risk of damage to the holds themselves. If other cargoes are carried, the stowage guides may be removed using ship's or shore-based loading or lifting gear and deposited in special holders on deck.

Securing in vessel holds by conventional securing and stacked stowage

On older, conventional general cargo vessels and multipurpose freighters, stacked stowage methods are used in the hold, combined with various securing methods:

|

|

| Example of stacked stowage with conventional securing |

The lower containers stand on foundations capable of withstanding the stack pressures which arise. Dovetail foundations, into which sliding cones fit, are provided to prevent slippage. The containers are connected together by single or double stacking cones or twist locks. The entire stack or container block is lashed using lashing wires or rods and turnbuckles. This system entails a lot of lashing work and material and, moreover, is less secure than securing in cell guides.

Securing in vessel holds by block stowage and stabilization

This securing method is found less and less frequently, but it is still found on some conbulkers and other multipurpose freighters. Containers are interconnected horizontally and vertically using single, double and possibly quadruple stacking cones. The top tiers are connected by means of bridge fittings.

|

|

| Fastening containers together |

To the sides, the containers are supported at their corner castings with "pressure/tension elements".

|

|

| Examples of block stowage method with stabilization |

This type of container securing has two marked disadvantages:

- If an individual container breaks, it is not just one container stack which is affected, but the whole container block.

- Due to dimensional tolerances and wear and tear to the stacking cones, the entire block can move constantly in rough seas. This causes the intermediate stacking cones to break and an entire block may collapse.

Securing on deck using container guides

On some ships, containers are also secured on deck in cell guides or lashing frames. Some years ago, Atlantic Container Lines used only cell guides on deck. Certain ships belonging to Polish Ocean Lines had combined systems. In other ships, cell guides can be pushed hydraulically over the hatch cover as soon as loading below deck is completed and the hatches have been covered up.

Securing on deck using block stowage securing

This method was used a lot in the early days of container ships, but has been used less and less in recent years for economic reasons.

|

|

| Example of block stowage securing on deck |

The containers in the bottom layer are positioned in socket elements or on fixed cones. Double stacking cones are used between the layers and the corner castings of adjoining containers are connected at the top by bridge fittings. The containers are held together over the entire width of the ship or hatch cover by cross lashings. A distinct disadvantage of this method is reduced flexibility when loading and unloading, since adjoining containers have always to be moved as well if access to a particular container is required.

Numerous variants, not listed any greater detail here, are available for attaching the lashings. Sometimes the lashings from different stacks cross one another.

|

|

| Crisscross lashings from different container stacks |

This securing method is being used increasingly in very large container ships.

Instructions for lashing on board ships are displayed in obvious places.

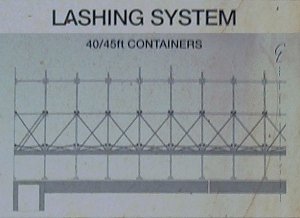

|

Lashing system for 40' and 45' containers |

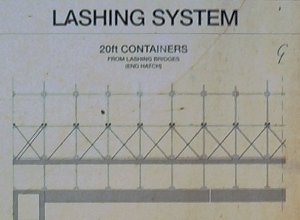

| Lashing system for 20' containers from the lashing bridges of the end hatches |  |

|

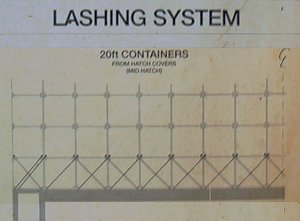

Lashing system for 20' containers from the hatch covers of the middle hatches |

Securing on deck using stacked stowage securing

This securing method is the one used most frequently. Cargo handling flexibility is its key advantage. The containers are stacked one on top of the other, connected with twist locks and lashed vertically. No stack is connected with any other stack. The container lashings do not cross over the lashings from other stacks, except for the "wind lashings" on the outer sides of the ship.

|

|

| Principle of stacked stowage securing |

|

|

|

| Securing of on-deck containers with lashing rods and twist locks | Securing of on-deck containers with twist locks and chains |

|

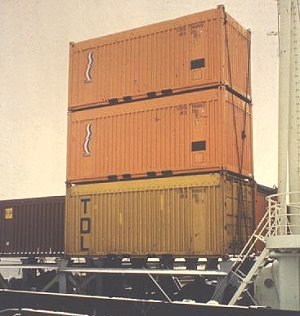

Securing of a 3-tier stack on board a semi-container ship |

Obviously, a container stack of this kind can topple if it is not adequately secured.

An absence of special equipment for securing containers and unfavorable stowage spaces increase the risk for container cargoes. "Sloppy" carriers should be avoided wherever possible. This applies quite generally, not only to the operators of aging ships. Timely information about as many as of the circumstances and procedures encountered during carriage as possible can be extremely useful.